A New Chapter for the U.S. Forest Service? Less Productive, Less Prepared, and Flying Blind

Wisconsin's Green Fire, July 3, 2025

A New Chapter for the U.S. Forest Service? Less Productive, Less Prepared, and Flying Blind

By Fred Clark and Paul Strong, WGF Members, Edited by Carolyn Pralle, WGF Communications & Outreach Coordinator

Editor’s Note:

This essay is adapted from an earlier version first published June 24, 2025 on This Land. Written by Fred Clark and Paul Strong, it is part of a series of longer pieces exploring changes for the U.S. Forest Service. WGF is publishing this adapted version as part of our efforts to track and document conservation changes at the federal level and interpret what those changes may mean for Wisconsin. Read the original essay here.

Fred Clark and Paul Strong are WGF members with expertise in forestry and conservation. Fred Clark was the former Executive Director of Wisconsin’s Green Fire and the Forest Stewards Guild with a career spanning public and private forestry work. In a 34 year career with the Forest Service, Paul Strong among other positions served as a Forest Planner, Regional Planning Director, and the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest Supervisor.

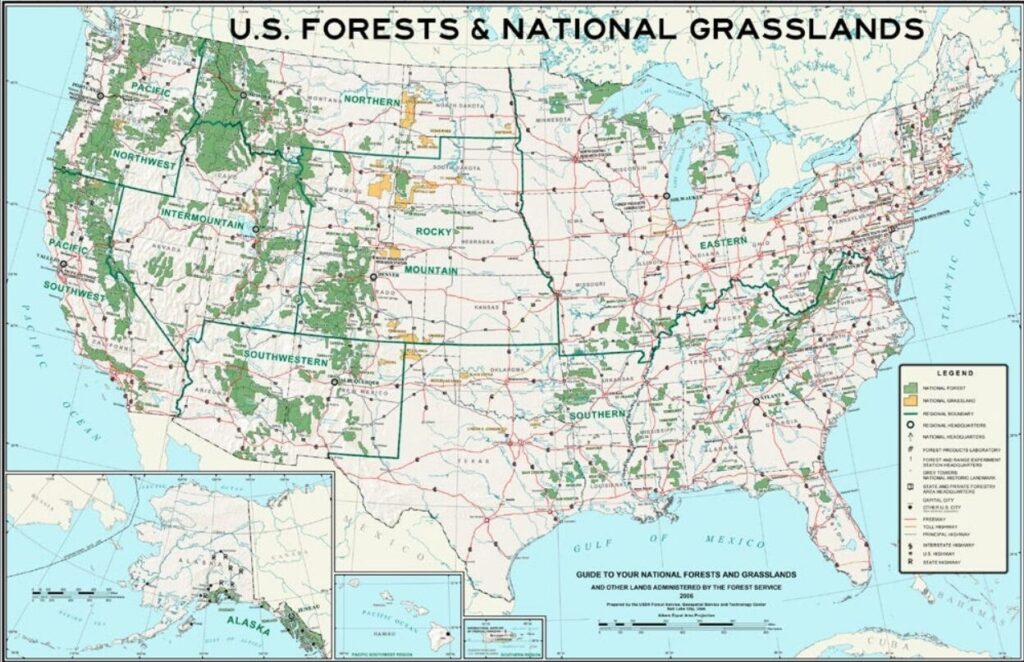

The 193 million acres of the National Forest System (NFS) comprise 154 national forests, 20 national grasslands, and other specially designated federal lands.

The President’s proposed 2026 budget for the United States Forest Service and his recent Executive Orders lay out a new vision for the Forest Service. In this vision, the Forest Service will be severely reduced in scope, capacity, and funding. It emphasizes timber production while other parts of the mission are de-emphasized or eliminated altogether. Taken as a whole, the proposed changes will make “caring for the land and serving people” (the Forest Service motto) more difficult by an order of magnitude.

Of all the ordered changes, we point to three which will create profound and long-lasting impacts.

- Increasing timber production on National Forest System Lands by 25% over 2020-2024 levels.

- Stripping fire management responsibilities from the Forest Service to a new Federal Wildland Fire Service agency housed in the Department of Interior.

- Closing down fundamentally important program areas including the Forest and Rangeland Research, and State, Private & Tribal Forestry functions.*

*A small number of these program functions, such as the Forest Inventory and Analysis program, will continue using carryover funds from 2025 and other previously appropriated funds.

Upping Harvest Levels

Increasing timber harvest levels by 25% is not an impossible goal. In fact, that level of increase would likely be within reach and could be accomplished consistent with the existing Forest Plans guiding many of our 154 National Forests. How the overall 25 percent increase will be directed to individual national forests is unclear. It is questionable whether or not the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest in Wisconsin could increase by a quarter its annual timber sale level of recent years and be consistent with the existing Forest Plan. One would expect that as a top timber-producing national forest over the last decade that little, if any, increase would be assigned to it, but it bears watching.

The National Active Forest Management Strategy document released by the Forest Service in May lays out the rationale and the methodology for achieving the goal, citing the economic benefits of timber production, and the need for forest fuels management and wildfire risk reduction. But now that the budget numbers, and the proposed 65% overall reduction in Forest Service funding (from $6.178 Billion to $2.136 Billion) have been laid out, we can see a clearer picture of the constraints on getting this extra work done. The line items in the President’s Budget warranting attention include a 34% reduction in Forest Service Operations, a 21% reduction in direct funding for the National Forest System (the home to those 194 million acres), and a complete loss of Wildland Fire Management Funding (more on that later).

Overall, budget reductions of these sizes will likely mean the loss through Reductions in Force (RIFS) of thousands of additional Forest Service staff on top of the roughly 4000 employees already departed via recent retirements, departures for other jobs, and firings, along with the loss of resources for equipment and operations needed to accomplish that broad-based mission. The loss of senior leadership and fire staff with Incident Command expertise will be especially felt as we enter the heart of the 2025 fire season.

So, how to overcome that huge drain of both managers and boots on the ground employees and still get even more work done? The National Strategy document calls on the agency to streamline the rules and regulations, and outsource more of the work.

Streamlining

Before implementing forest management projects through commercial timber sales, the Forest Service conducts environmental analyses required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and in concert with other laws including the National Forest Management Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Clean Water Act.

The National Active Forest Management Strategy calls for use of exemptions, categorical exclusions, and emergency declarations to simplify planning and avoid the use of Environmental Assessments or Environmental Impact Statements that larger and more complex projects typically require. Such a mandate takes away the judgment and discretion of local line officers to develop efficient approaches to required environmental planning. It also risks more legal challenges.

Further complicating things for an agency that is about to be dramatically downsized, is that the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) in February announced it was rescinding its NEPA implementing regulations that guide all federal agencies. This forces agencies to go back and write new rules to comply with the NEPA law.

Outsourcing

The Forest Service has long relied on logging and construction contractors to harvest timber, build roads and bridges, and other specialized work, and relied on contract timber marking to supplement FS in-house marking crews. Since 2015 a newer tool, Good Neighbor Authority, has been used to more broadly outsource timber sale setup, marking, and administration to State Forestry agencies. The National Strategy calls for increased use of Good Neighbor Authority through states, counties, and Native American tribes, as well as use of more longer term Stewardship Contracts that turnover a wider swath of project implementation and oversight to private and NGO contractors.

With limited resources and time, this approach will likely eliminate what would otherwise be efficient and cost-effective opportunities to accomplish wildlife and fish habitat improvement, restoration of non-forest habitats, recreational site activities, or much needed soil and water improvement projects in order to avoid the additional planning effort that work would require. We can expect to see much less work on the resources and values that the vast majority of American citizens want most from their national forests.

Moving Fire out of the Forest Service

The President’s proposal to strip all fire management functions and funding out of the Forest Service and into a new Federal Wildland Fire Service may create some efficiencies on paper. But it threatens to result in higher fire risks and reduced health on those 193 million acres of National Forest lands, and a greater burden on states and local governments and private landowners.

Currently, federal responsibility for wildland fire is spread among at least five agencies: the Forest Service (which is the largest federal wildfire agency), Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Indian Affairs. Each has a distinct land base to both manage for and protect from fire. Training, logistics and response to large fires throughout the country are coordinated among the agencies and state and local partners by the National Interagency Fire Center. In Wisconsin, the key wildfire prevention and response partnership is between the Forest Service and the Wisconsin DNR. How the proposed change would affect this important business arrangement is unclear and not optimistic.

As the largest federal wildfire agency, the Forest Service has thousands of employees with primary fire management assignments, and thousands more who have other primary assignments but who have fire training and can be called on to serve on fires when needed. This extra flex force actually uses people and resources pretty efficiently. It also helps assure that our National Forests have the capacity in house to conduct prescribed fires and other work needed to reduce fire risk – all outcomes called out as priorities in the recent National Strategy.

Moving all fire management and the 9000 or so wildland firefighters and their resources into a new Federal Wildland Fire Service in the Department of Interior will alone strip 40% ($2.4 Billion) out of the Forest Service Budget, most of which will come from reassignments of National Forest System staff. The efficiencies from those flex employees will likely be lost, and the ability of National Forests to manage their own lands for fire prevention effectively will likely be compromised as the capacity to accomplish that work will now reside in an entirely different department.

In addition to the impact on National Forests, the budget also takes a swipe at important programs supporting community fire preparedness on local government and private lands. The budget cuts $50 million in funding to the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program that supports appropriate forest management on priority landscapes across the country, many of which are in high fire risk areas. This bold and forward thinking program engages communities and gives them a greater stake in economic and environmental outcomes on nearby federal lands, and on local government, tribal, and private lands.

Leaving States, Tribes, and Private Forest Landowners Hanging

The Forest Service has long played a role outside of National Forests supporting states, tribes, and private forest owners with technical and financial assistance. The 2026 budget eliminates all new appropriations for the State, Private & Tribal Forestry programs ($283 Million in 2025).* *A small number of program functions will continue using carryover funds from 2025.

Nowhere does the current budget offer even minimally adequate resources for states, local governments, or Tribes to assume the greater role envisioned for them. The scale of cuts suggests that forest health protection, technical assistance to private landowners, wood use innovation, and support of urban and community forests would all be significantly diminished or eliminated.

Not only is this Administration abandoning many of the values of federal forest land, but it is leaving Tribes, States, and private landowners hanging by drying up much of the federal assistance of money, technical expertise, and staff time.

The War on Forest Science

The Forest Service Research and Development Program is the world’s largest natural resources research agency. Trump’s budget calls for cutting funding for the Forest Service Research Program in its entirety. The loss would be 800 or so scientists and staff researchers who conduct important research work on forest management, wildfire prevention and management, climate change, fish, wildlife and biodiversity, recreational forest uses and myriad other forest-related issues. Only the Forest Inventory and Analysis part of R&D will remain. The Forest Service Research facility in Rhinelander would be closed down and the dozen or so researchers and field technicians would be laid off, presumably as part of the agency reorganization and reduction in force plans. It is difficult to calculate the losses that would result from the termination of research projects, many of which have been built across several decades, and all of which support sustainable forests.

Included with the Research Program elimination would be the elimination of the Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory in Madison.

Since 1910, the Forest Products Laboratory (FPL) has tested and helped improve performance for traditional wood products and conduct applied research on new wood products. FPL researchers study pulping and papermaking, test the compression and tensile strengths of timbers, and develop and refine new applications for wood products such as mass timber panels, biochar, and wood-based nanofibers. As the only facility of its kind in North America, closure of the Forest Products Laboratory would badly hurt the development of new uses for forest products just at a time when we most need to develop more uses for wood to help counter the loss of traditional forest products markets.

In this new normal of rapidly changing climate, more intense and frequent fires and other natural disasters, Forest Service Research represents a practical investment in applied research that supports smart forest management for the future.

What’s Next

Taken together, the 2026 Forest Service under this budget will be unrecognizable: less capable of effectively managing its own land base, less prepared to serve the public during emergencies, less supportive of Tribes, States, and private landowners, and unable to be visionary or influential in a time of increasing disturbance and uncertainty for forests. If the push to produce timber above all else remains the primary objective, it seems inevitable that privatization of management functions (timber management) and/or wholesale divestiture of land will be on the horizon soon.

Although the current proposals in Congress to tee up large scale federal land sales appear dead for now, the President’s budget opens the door with a “land transfer initiative” to states and tribes. Among all the directives being given to the Forest Service, it seems that the measurable few are to “Cut the Budget,” “Cut the Workforce,” “Cut the Paperwork,” and “Cut More Timber.” Achieving those goals will result in forests that are less healthy, less diverse, and less resilient, and will offer many fewer opportunities for meaningful public engagement.

The Nature Conservancy, The Wilderness Alliance, and the Trust for Public Lands all have advocacy pages where you can learn more and take action.